Can Type III hard-anodized (hardcoat) surfaces be dyed?

As a manufacturing engineer specializing in surface treatments, this is a fundamental question of process capability. The direct and technically precise answer is no, Type III hard-anodized surfaces cannot be practically or effectively dyed in the conventional sense. While the coating is porous immediately after anodizing, its inherent physical characteristics make it unsuitable for standard dyeing processes. However, this "limitation" is precisely what gives hardcoat its exceptional functional properties, and there are alternative methods to achieve color.

Manufacturing Process: Why Dyeing Is Ineffective

The inability to dye hardcoat is a direct consequence of the process parameters used to create it, which differ significantly from those used for decorative (Type II) anodizing.

The Nature of the Type III Coating

Hard Anodizing, or Type III anodizing, is an electrochemical process performed at a much lower temperature and higher current density than Type II. This results in a coating that is substantially thicker, denser, and harder. While it does create a porous surface structure, the pores are significantly smaller and shallower than those in a decorative anodic layer. These minute pores cannot adequately absorb or retain standard liquid dyes.

The Primary Focus: Sealing for Performance

The primary goal of hard anodizing is to maximize surface hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion protection. Immediately after the anodizing process, the coating is sealed to permanently close these micro-pores. This sealing process is crucial for enhancing the coating's corrosion resistance by preventing the ingress of contaminants. Dyeing, which must occur after anodizing but before sealing, is incompatible because the dye molecules cannot effectively penetrate the dense, hardcoat structure.

Comparison to Decorative Anodizing

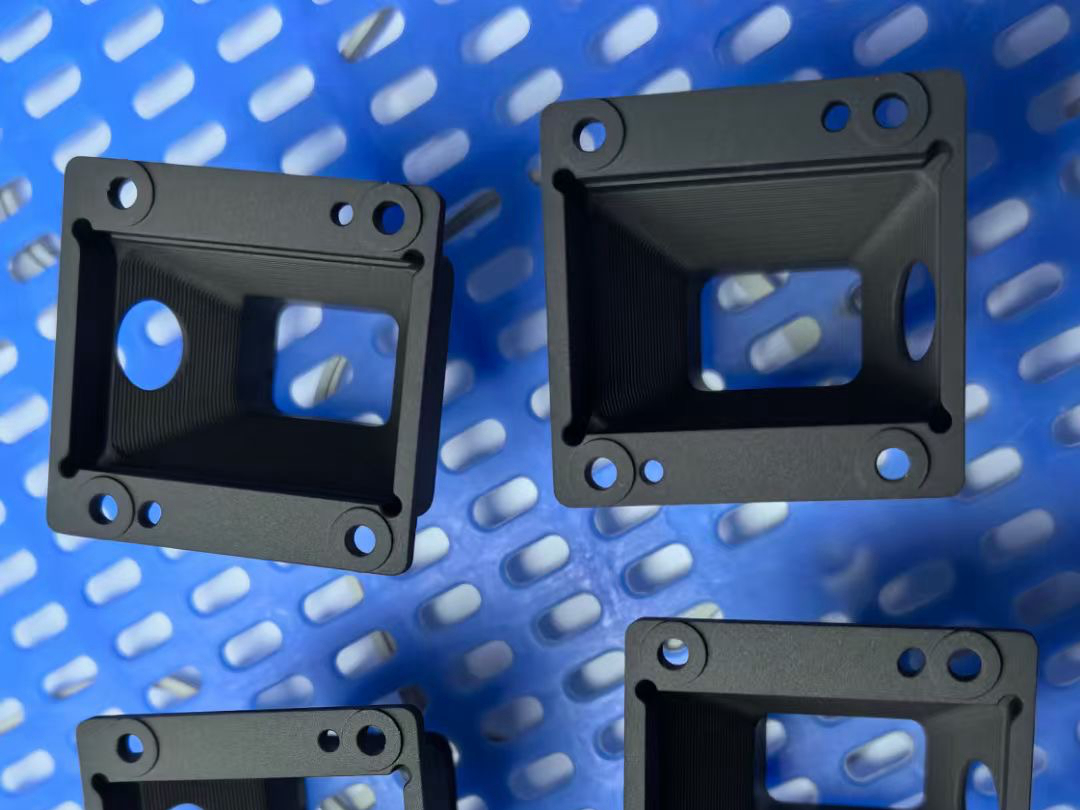

In contrast, standard Anodizing (Type II) produces a more open and absorbent porous layer specifically designed to accept dyes. The process conditions are optimized for dye uptake, making it the standard method for achieving black, colors, and other decorative finishes.

Post-Process Alternatives

Since integral dyeing is not feasible, applying a color to a hard-anodized part requires a secondary, superficial process. One common method is Die castings Painting, where a specialized paint adheres to the hard surface. Another robust alternative is Die castings Powder Coating, which can provide a durable, colored layer on top of the hardcoat, combining the wear resistance of the substrate with color.

Surface Treatment: Functional Properties Over Aesthetics

The design choice for hard anodizing is almost always driven by engineering requirements rather than aesthetics.

Inherent Color of Hard Anodizing

Due to the thickness of the coating (often 50 μm or more) and the process parameters, Type III hardcoat has an inherent color ranging from a dark gray to a blackish-brown or even a bronze hue. The exact shade depends on the specific aluminum alloy, the anodizing parameters, and the coating thickness. This natural color is often sufficient for industrial applications where performance is paramount.

When Color is a Functional Requirement

In some cases, color is needed for functional reasons, such as for heat absorption or part identification. In these instances, the secondary coating processes mentioned above (painting or powder coating) are the correct solution. The hard-anodized layer provides an excellent, stable, and adherent substrate for these organic coatings.

Materials: The Role of Aluminum Alloy

The base material significantly influences the final characteristics of the hard-anodized layer, including its natural color.

Alloy Impact on Coating Appearance

The natural color of a hard-anodized surface is heavily influenced by the alloying elements. For instance, hard anodizing high-purity alloys like A356 will yield a more uniform dark gray appearance. In contrast, anodizing high-silicon alloys like A380 or A360 results in a darker, often mottled gray appearance because the silicon particles remain unanodized and are embedded in the coating.

Material Selection for Performance

The choice of alloy is therefore critical when planning for a hard-coat finish. For a more uniform appearance of the hardcoat, an alloy with lower impurity levels is preferred. Our Die Cast Aluminum Alloys page provides detailed information to guide this selection based on the final application requirements.

Industries: Applications Demanding Hardcoat

Hard anodizing is specified in industries where component survival in harsh environments is more critical than color.

Automotive and Aerospace

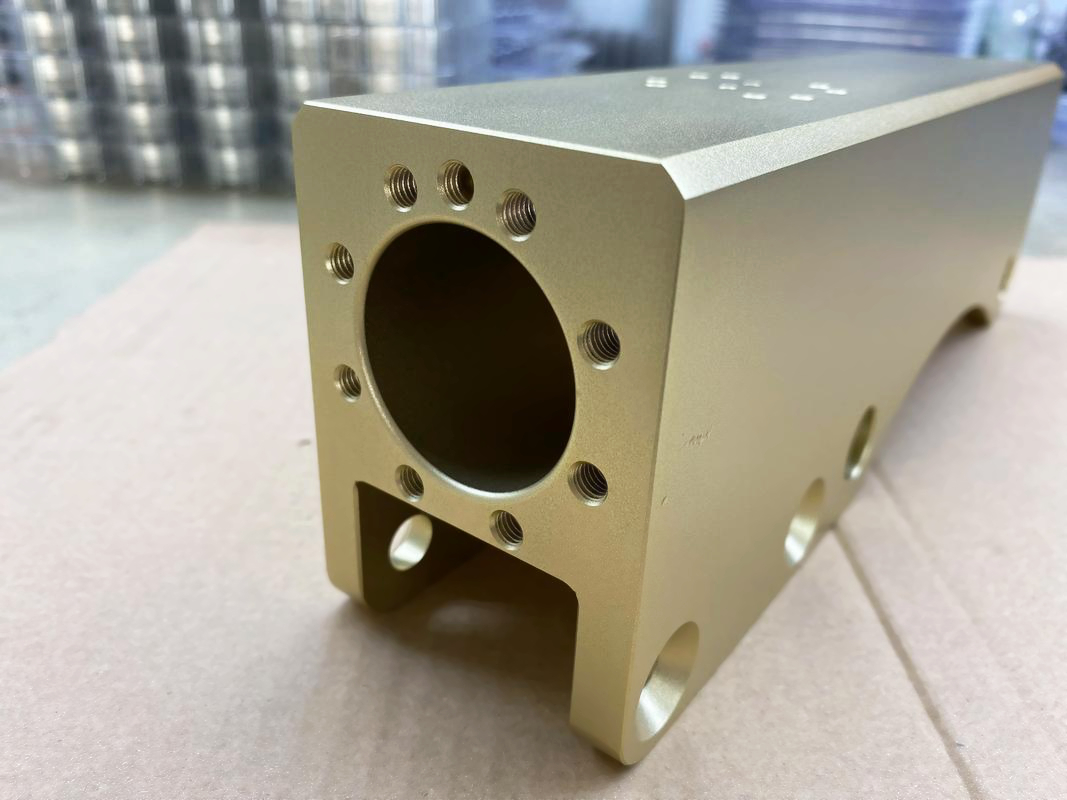

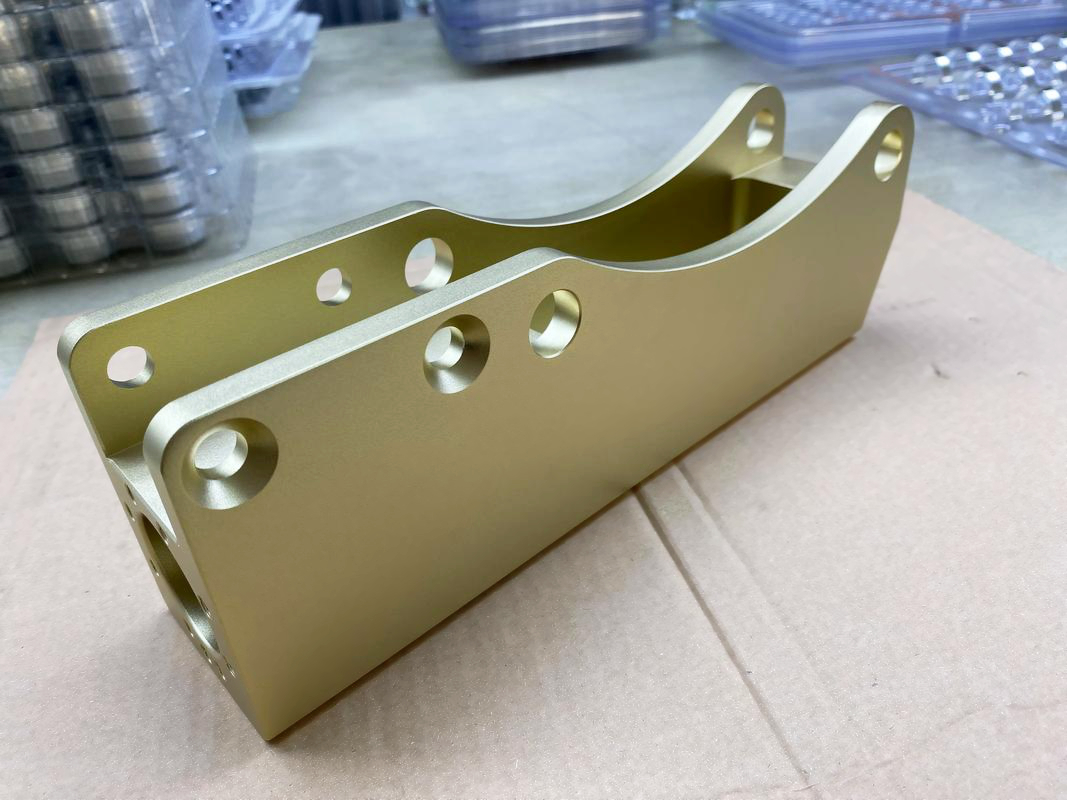

In automotive and aerospace applications, components such as pistons, valve bodies, and hydraulic components require exceptional wear resistance. Our work in Custom Automotive Parts often involves hard anodizing for functional surfaces, where its natural dark color is perfectly acceptable.

Industrial Machinery and Tools

For parts subject to constant abrasion, such as Bosch Power Tools components, hydraulic cylinders, and bearing surfaces, the unparalleled hardness and low coefficient of friction of hard anodizing are the primary design drivers, making dyeability irrelevant.

Military and Defense

Military specifications (such as MIL-A-8625) frequently call for Type III hardcoat on equipment where durability, corrosion resistance, and non-reflective surfaces are mandatory. The inherent dark color of the coating is often a benefit, not a drawback.

Conclusion

In summary, Type III hard-anodized surfaces cannot be dyed due to the dense, non-absorbent nature of the coating itself. This characteristic is a direct result of the process parameters that give hardcoat its exceptional functional properties. When color is required on a component that also requires the performance of a hard coat, the solution is to apply a secondary coating, such as paint or powder coating, over the anodized surface. The choice between decorative Type II anodizing and functional Type III hard anodizing is a fundamental design decision that balances aesthetic needs against performance requirements.