Does anodizing affect the mechanical properties of aluminum alloys?

As a manufacturing engineer specializing in material science and surface treatments, I can confirm that anodizing has a complex and multifaceted effect on the mechanical properties of aluminum alloys, with both beneficial and detrimental impacts. The most significant influence is often on the material's fatigue strength, which can be reduced if the process is not properly controlled and understood. However, the process also confers major advantages that are critical for component performance.

Manufacturing Process: The Core of the Interaction

The anodizing process itself is the primary factor determining the final mechanical outcome. It is not a simple coating but a transformation of the base material.

The Electrochemical Transformation

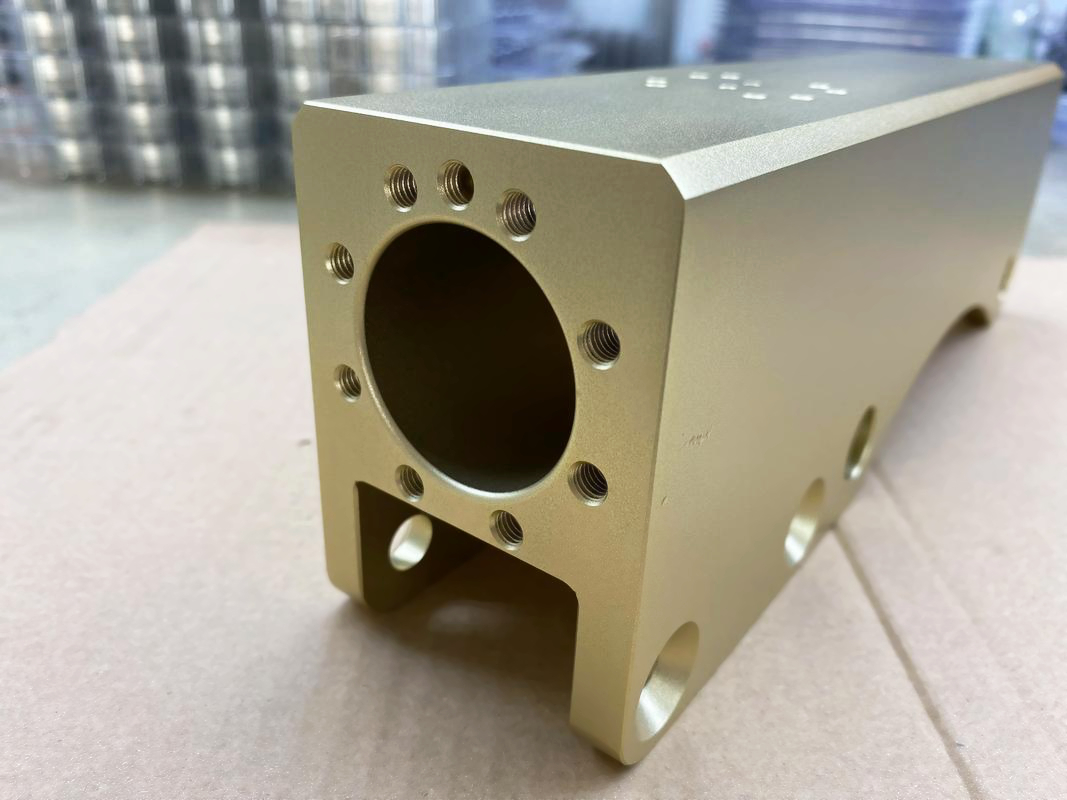

The Anodizing process converts the outer layer of the aluminum substrate into a hard, porous aluminum oxide ceramic. This newly formed layer is integral to the part but has vastly different mechanical properties. It is exceptionally hard and wear-resistant but also more brittle than the underlying ductile aluminum.

Stress Concentration and Notch Sensitivity

The key detriment to fatigue strength arises from the geometry of the anodic layer. The interface between the brittle anodic coating and the ductile aluminum core can act as a stress concentration point. Under cyclic loading, micro-cracks can initiate at this interface and propagate into the base material, leading to a reduction in fatigue life. This effect is more pronounced with thicker coatings, such as those produced by Hard Anodizing (Type III).

The Critical Role of Surface Preparation

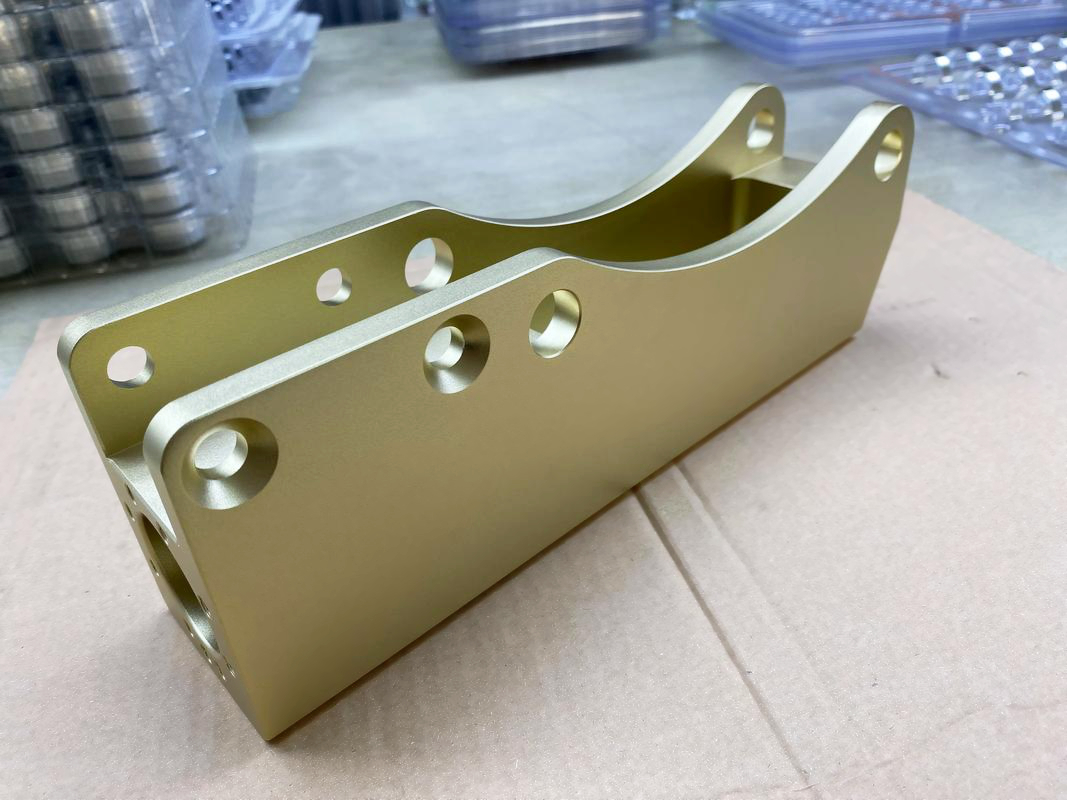

The condition of the aluminum surface before anodizing is paramount. Processes like CNC Machining or Die castings Post Machining must produce surfaces with low roughness and, critically, without sharp corners. A sharp corner will concentrate the anodic coating, creating a natural notch that severely compromises fatigue performance. Designing generous fillets is essential.

Mitigation Through Process Control

The negative impact on fatigue can be mitigated. A well-controlled anodizing process that produces a consistent, fine-pored structure is less detrimental. Furthermore, certain post-treatments, like the impregnation with Teflon or other dry lubricants sometimes used in hard coat, can slightly alter the surface stress state.

Surface Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword

The mechanical changes induced by anodizing present a trade-off that must be carefully evaluated against the requirements of the application.

Enhanced Surface Properties

The primary mechanical benefit is a dramatic increase in surface hardness. An anodized layer, especially a hardcoat, is significantly harder than the base aluminum, providing exceptional resistance to abrasion and wear. This is a key reason it is specified for components like hydraulic pistons and high-wear guides.

Comparison with Other Finishes

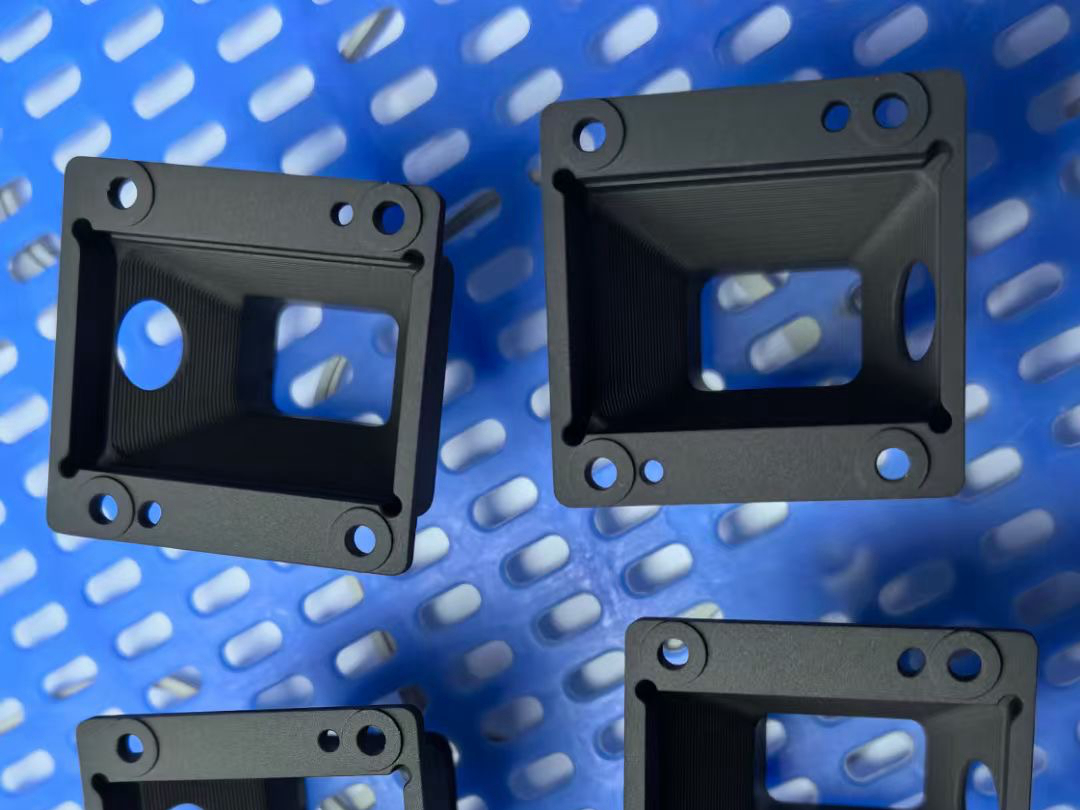

Unlike an applied coating like Painting or Powder Coating, the anodic layer is part of the substrate. While paints can fill scratches and hide surface imperfections, anodizing will replicate the underlying surface topography. Therefore, any surface defects on the aluminum will be preserved and can still serve as initiation sites for fatigue cracks.

Materials: The Alloy's Crucial Influence

The specific aluminum alloy being anodized plays a significant role in determining the magnitude of the effect on mechanical properties.

Alloy Composition and Coating Quality

Alloys with high copper content (e.g., A380) or high silicon content (e.g., A360) present challenges. The intermetallic particles formed by these elements do not anodize well, leading to a less uniform coating with embedded particles. This inhomogeneity can further exacerbate stress concentrations and reduce fatigue performance compared to anodizing a purer, more homogenous alloy like A356.

The Substrate's Inherent Strength

The anodizing process is performed at relatively low temperatures and does not significantly heat-treat the part. Therefore, the core mechanical properties of the aluminum—such as its yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and modulus of elasticity—remain largely unchanged. The anodic layer only affects the properties of the surface and the interface.

Industries: Weighing the Trade-Offs in Application

The decision to anodize is a calculated one, where the benefits of surface hardness and corrosion resistance are weighed against the potential reduction in fatigue life.

Aerospace and Automotive

In these highly weight- and performance-critical industries, the fatigue debit is a major concern. Anodizing is used selectively. It may be applied to non-structural components or to areas where wear is the primary failure mode. For critical load-bearing structures, extensive testing is required, and processes like Die castings Engineering are vital to simulate and validate the design.

Consumer Electronics and Hardware

For components like the hinge in the Apple Bluetooth Wireless Earphone project, the wear resistance and aesthetic benefits of anodizing are paramount. The cyclic loading on such a hinge is typically well within the limits where a properly applied, thin anodic coating does not pose a fatigue risk.

Industrial Machinery

For components in Bosch Power Tools, which experience high loads and impacts, hard anodizing is invaluable for preventing galling and wear on housings and gears. The design must account for the brittle nature of the coating and potential fatigue effects through robust geometry and material selection.

Conclusion

In summary, anodizing affects the mechanical properties of aluminum alloys, most notably by potentially reducing fatigue strength due to the introduction of a brittle layer and stress concentration at the interface. However, this is balanced by a tremendous increase in surface hardness and wear resistance. The key to a successful application lies in intelligent design (avoiding sharp corners), proper process control, and selecting the right alloy. For critical dynamic applications, prototyping and testing are non-negotiable.