Why do A380 and ADC12 alloys show color variations after anodizing?

The visual inconsistency you observe is not a defect of the anodizing process itself, but rather a direct reflection of the heterogeneous microstructure of these specific alloys. A380 (a US standard) and ADC12 (its common Japanese equivalent) are designed for excellent castability and strength at the expense of perfect anodizing aesthetics. The variations stem from how the anodic layer interacts with the alloy's intermetallic compounds.

Manufacturing Process: Amplifying Underlying Inhomogeneity

The anodizing process acts as a microscope, revealing the otherwise invisible composition of the metal.

The Anodizing Reaction

Anodizing is an electrochemical process that converts the aluminum surface into aluminum oxide. This new layer is transparent. However, the reaction is highly selective, occurring only with the aluminum matrix and not with non-aluminum elements.

The Role of Silicon Particles

Both A380 and ADC12 contain between 7.5% to 9.5% silicon, along with significant copper and iron. During solidification in the Aluminum Die Casting process, these elements form hard, intermetallic particles (primarily silicon and Al-Fe-Si-Cu phases). These particles are electrochemically inert; they do not anodize.

Resulting Surface Topography

After anodizing, the aluminum matrix is converted into a porous, transparent oxide, while the silicon and other intermetallic particles remain embedded within this layer or are exposed. This creates a microscopically rough and inhomogeneous surface. Light reflecting from this complex surface—scattering off the transparent oxide, the embedded silicon, and the underlying aluminum—results in a dull, grayish, and often mottled or "speckled" appearance. This effect is universal for high-silicon alloys but can vary between batches due to subtle differences in solidification rates.

Materials: The Core of the Problem

The fundamental issue is the alloy chemistry, which is optimized for casting, not finishing.

High Silicon Content for Castability

The high silicon content in alloys like A380 is what makes them so free-flowing and suitable for producing complex, thin-walled die castings. Unfortunately, this very property is detrimental to achieving a uniform anodized finish.

Comparison with Anodizing-Grade Alloys

Contrast this with an alloy like A356 (typically used for gravity and low-pressure casting). A356 has a much lower silicon content (6.5-7.5%) and tighter control over impurities like iron and copper. Its microstructure is more homogeneous, resulting in a clear, bright, and highly uniform anodic layer that accepts dyes vibrantly and consistently.

Surface Treatment: Limitations and Mitigations

Understanding the cause allows for better planning and some degree of mitigation.

Inherent Limitations with A380/ADC12

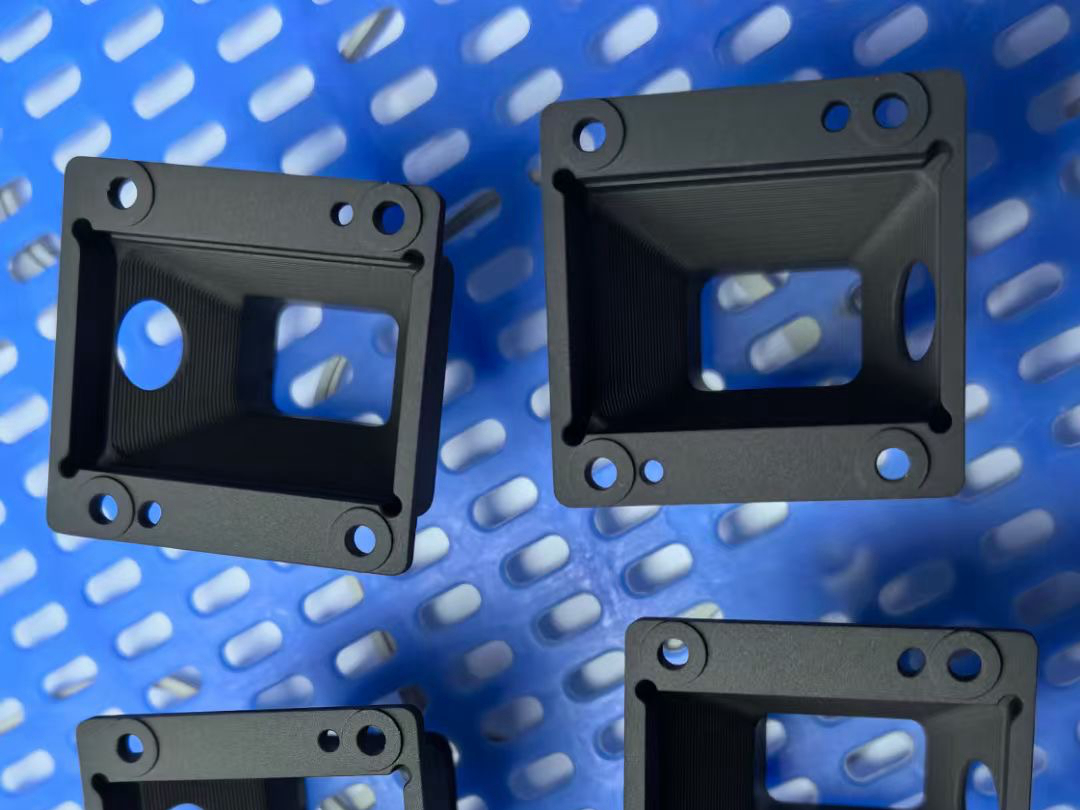

It is crucial to understand that you cannot achieve a perfectly uniform, bright, or clear anodized finish on A380/ADC12 as you can on a purer alloy. The variations are inherent. Darker colors, especially black, are better at masking these variations, while clear and light colors (like silver, gold, or light bronze) will make the speckling and non-uniformity most apparent.

Process Optimizations

While the fundamental issue is material-based, process optimizations can help reduce extreme variation. Excellent Die Castings Engineering can optimize the casting process to create a finer, more uniform distribution of silicon particles. Additionally, specific Post Process treatments, such as specialized chemical polishing or electro-polishing before anodizing, can help smooth the surface and slightly improve uniformity, though at an added cost.

Industries: Managing Expectations for Application

The choice to use A380/ADC12 is a calculated trade-off between cost, performance, and aesthetics.

Functional vs. Cosmetic Applications

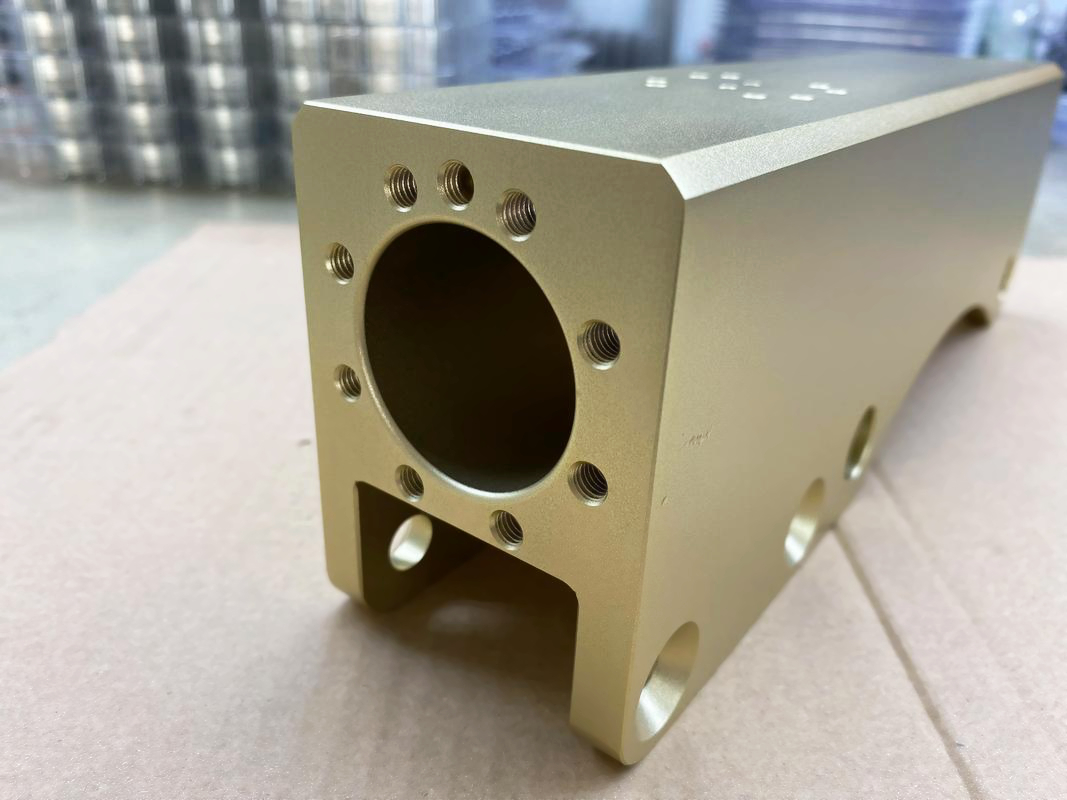

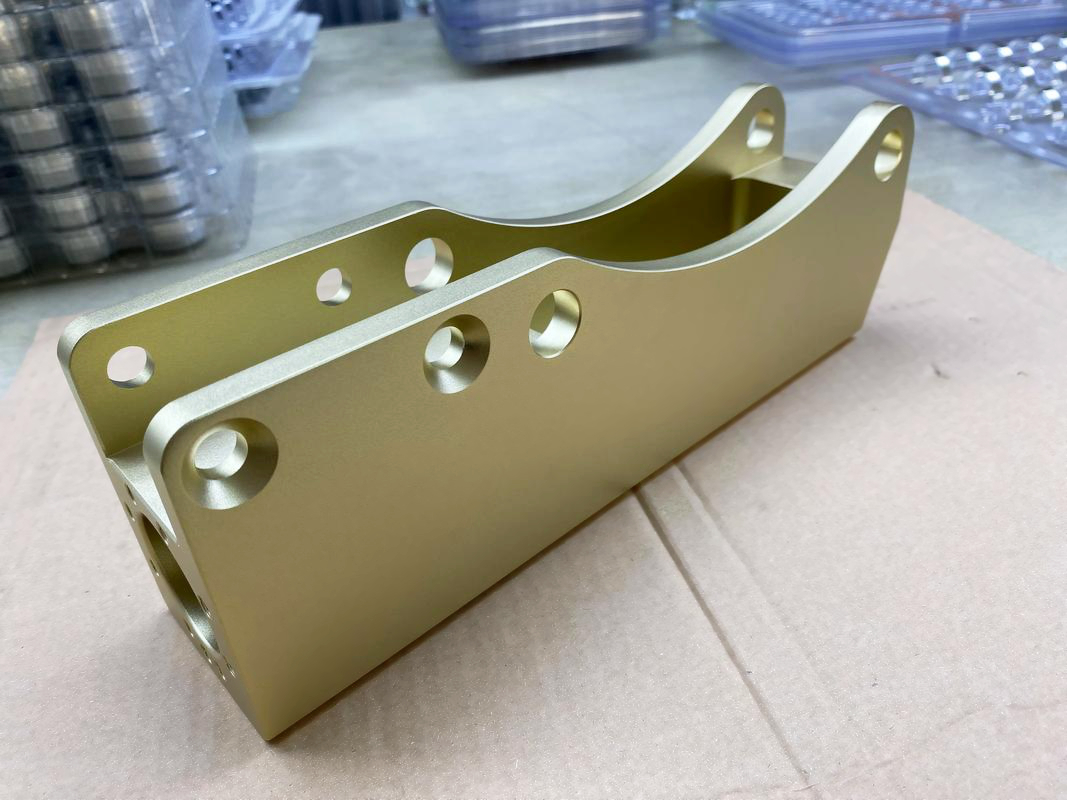

The A380/ADC12 is perfectly suitable for anodizing when the primary requirement is corrosion resistance and wear resistance, with cosmetic appearance being secondary. This is common for internal components, mechanical housings, and parts where the finish is more functional than decorative.

When Cosmetic Perfection is Required

For consumer-facing products where a perfect, uniform aesthetic is critical (e.g., the exterior housing of a premium smartphone or a architectural trim), specifying A380/ADC12 for anodizing is not recommended. In such cases, a switch to a more suitable alloy like A356 or a change in the finishing method to Powder Coating or Painting would be the appropriate engineering decision.

Conclusion

In summary, the color variations observed in anodized A380 and ADC12 are a direct result of their high silicon and copper content. The inert silicon particles create a microscopically inhomogeneous surface that scatters light unevenly. This is a material property, not a process failure. For applications requiring a uniform and bright anodized finish, selecting an anodizing-grade alloy from the outset is critical.